The long-time colleague of Jane Jacobs writes in the New York Review of Books that “This is a New York story only for now” and “Upzonings and transfers of newly created air rights are occurring slowly in cities around the country.”

In yet another timely warning to Portland and other cities, Roberta Brandes Gratz, the long-time friend and colleague of activist and urban champion Jane Jacobs, describes the dangers of reckless upzoning and transfer rights:

I weep for my city; it is committing urban suicide. I am a daughter of Gotham, born and bred. My lifelong interest in the vitality of the city included a thirty-year friendship with famed urbanist Jane Jacobs, with whom I, and a small group of activists, founded the Center for the Living City to build on her legacy…

This is a New York story only for now. Upzonings and transfers of newly created air rights are occurring slowly in cities around the country. When it comes to real estate, New York City may lead the way, but others follow in time.

It appears that Portland is already following this path, notably in the adoption of the Better Housing by Design ordinance, which was opposed by Commissioner Amanda Fritz in a stinging critique (covered in the current Northwest Examiner on Page 1).

Gratz points out how progressive goals like sustainability become a mockery under these and similar “deregulatory upzonings:”

In 2018, Chase Bank announced that it would tear down the fifty-two-story, black-and-silver-ribbed, early Modernist tower at 270 Park Avenue in order to build a new tower at least seventy stories high. This will be the tallest-ever demolition of a perfectly viable building in New York City. In 2002, Chase began a total renovation of the building to LEED standard, a green building certification that gave it “platinum” status, a rating that acknowledges the value of preserving the embodied energy of an existing building and avoids energy use for demolition, landfill, and new construction. Landmark skyscrapers across the country—from the Empire State Building, Chicago’s Willis Tower (formerly Sears), and San Francisco’s Transamerica—have taken this environmentally responsible approach and upgraded their buildings to LEED platinum standard. And in doing so, Chase also benefitted from the five years of federal environmental tax credits that go with that designation. Then threw it all away.

To achieve the extra height and bulk of the new 270 Park, Chase is taking advantage of the “upzoning” of nearby mid-Manhattan that was applied in 2017 to a seventy-three-block area around Grand Central between 39th and 57th Streets. Upzoning’s relaxation of city planning regulations expands the development potential of new buildings by allowing increased height and density (the number of units or amount of floor area on a given lot), and simplifying the transfer of “air rights” from landmarked buildings to new sites within the district. (Air rights are the so-called unused development rights that would allow a hypothetical taller building on a particular lot, but they can be transferred by sale from one lot to another, depending on the district’s zoning designation.) A portion of any air rights sale does go into a city fund specifically for area subway and pedestrian improvements—but, in this case, that would be for an area already jammed with pedestrians.

Chase was thus able to buy air rights from the landmarked St. Patrick’s Cathedral, some six blocks away, and construct a taller, bulkier building. Preservationists have identified at least thirty-three buildings worthy of landmark protection from such redevelopment in this Midtown district, but after fierce resistance from real estate interests, only twelve have been so designated. By no logic—design, environmental, planning, zoning, landfill capacity—does demolition of 270 Park make sense, especially when at least some in the architectural community are trying to advance sustainable design…

Gratz also stresses the importance of a healthy urbanization process, something that Jacobs was careful to articulate:

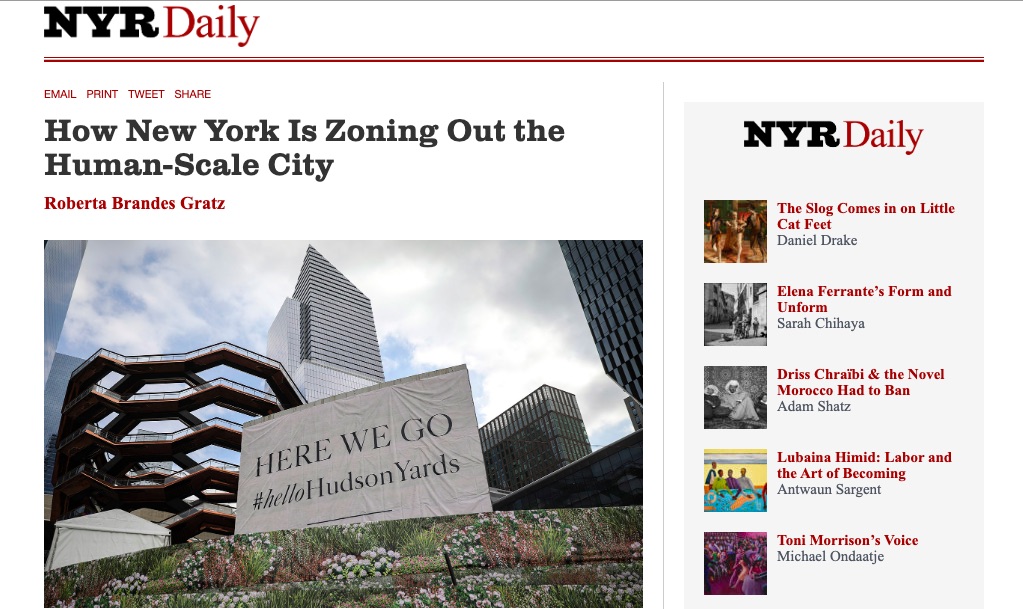

Writing almost sixty years ago, Jacobs drew a distinction that warned of the difference between gradual evolution that does not disrupt a city and “cataclysmic” change that threatens a city’s fabric. The alteration we witness today is cataclysmic. Hudson Yards, the new mega-development on Manhattan’s far West Side, is only the most glaring example, but the supertall towers that are spreading like kudzu elsewhere are an increasingly visible disgrace. It is all a reflection of the stranglehold of big real estate interests, with their power to manipulate the zoning code beyond reason. Hudson Yards represents a kind of privately controlled gated community in the sky—definitely a cardinal sin of urbanism—but even more significant, from my perspective, is 270 Park.

Urbanism is the uneven process that creates cities, over time and organically, through a confluence of democratic, economic, and social forces. This is what Jacobs called an “urban ecology.” This same process can also rebuild and strengthen even troubled cities today, if given a chance, and if big profit-driven real estate interests are not the overriding force in urban development. But authentic urbanism is a process, not a project subject to a design or plan. The result is a balanced mix of buildings and uses resulting in a built environment at human scale. That is precisely what is being lost today in New York City.

In a description that could apply to other cities (including Portland), Gratz describes a “perversion” of the public process, including the provess of establishing historic landmarks:

The redevelopment of 270 Park Avenue, which has slipped under the radar of public attention, is an alarming precursor of things to come. It is characteristic of the way the city is committing urbanism suicide, a death by a thousand smaller, self-inflicted cuts. And it reflects how real estate owns and controls a city that is supposed to run on democratic principles.

First is an underrecognized perversion of the landmarking process. Originally, landmarked buildings were awarded air rights to compensate for their owners being prevented from tearing them down and rebuilding on the same site. Those air rights, though, could be transferred to a building adjacent or opposite. Air rights from landmarks were never meant to float afar. A major consequence of the upzoning, though, is that air rights have now become transferable to increasingly distant lots…

Gratz spares no criticism of the New York development community and its “strange bedfellows” in the public sector:

There appear to be no limits to what the development community gets away with. They’ve taken effective control of both the City Planning Commission and the Board of Standards and Appeals (BSA). They have also succeeded in intimidating and taming the Landmarks Preservation Commission, restraining its original mission and turning its system of historic tax credits attached to landmark buildings to new commercial advantage. They are so in control, their machinations are not even hidden…

In another disquieting parallel to Portland and other cities, Gratz points out the egregious fallacy of local claims for building heights as a strategy to promote affordability:

Advocates of upzoning argue that it is needed to allow construction of taller buildings to create new affordable housing units. Real estate interests’ upzoning mantra perpetuates a confusion that height creates density. This is a dangerous myth. Along with many American cities after World War II, New York experienced years of demolition and de-densification in the name of “urban renewal.” This misguided movement, often acting in the name of “slum clearance,” used the concept of “towers in the park” to replace old neighborhoods that had grown up organically around a density of mixed uses—residential, businesses, factories, markets. “Urban renewal” demolished existing communities, never replacing as many housing units as had previously existed.

Gratz calls for a more cautious assessment of the impacts of unchecked upzoning, and the potential for better alternative development in the many empty sites in the city. She closes by calling for a vigorous campaign to that end:

If we continue to allow the erosion of the human-scale city and long-evolved urbanism on which it depends, then I fear for the future. The first thing needed is a public exhibit of the many empty sites across the boroughs of New York, and a representation of what further, unchecked upzoning will it make possible to build in the future. But without a well-organized, well-financed campaign like the effort to save Grand Central, or a singular leader like Jane Jacobs able to take on the powers that be and a press willing to give these battles full coverage, the perilous undermining of authentic urbanism will continue.

The full article is worth a careful read, and available here.